To celebrate our 50th anniversary, we’ve asked some of the folk who’ve helped bring Greenbelt Festival to life over the last 50 years to write a little something about their festival experiences. One blog post per month, reflecting on one decade at a time.

Last month, Dot Reid and Nick Welsh wrote about the 1990s. This month it’s the turn of Andy Turner to take us back to the 2000s, a decade that saw the rebirth of Greenbelt at Cheltenham Racecourse.

Worship & Spirituality Shrines, 2002

Greenbelt in the late nineties and early noughties was exhilarating and exhausting.

Exhilarating because of the sheer determination to survive – the appetite to experiment spun the festival in all kinds of new directions. Greenbelt took risks, “tried out”, reimagined, collaborated, even shifting to a racecourse-weekend in July for-crying-out-loud.

Exhausting, because it rained.

There is something about the patter of rain on your tent at 3am over an August Bank Holiday weekend, that Melts. Your. Brain. Late 90s Greenbelt was a rain magnet, a festival for waterproofs, wellies and people who queued, listened to John Bell, ate lunch, cooked dinner, watched Mainstage, and went to sleep, in the rain.

The idea of a racecourse venue, pitched by the then festival director Andy Thornton, was a light bulb moment – think carpet, concrete, parade ring as stadium for brilliant music. The fact only a handful showed up to the first one (in 1999), and the mainstage nearly blew away a few years later were tiny setbacks. The shift set the pace for a decade of imagination, and activism. The “urban” site welcomed new audiences – non-campers happy to hotel-it nearby. And Greenbelters, uneasy about change, found their way back.

A Greenbelt noughties playlist is chock full of stunning artists and performers, thinkers, and doers. Read previous blogs, and add Jamelia, Athlete, Cornershop, Spearhead or Body Shop founder Anita Roddick, and campaigner Peter Tatchell. Alongside contributors, Greenbelt had an impossible, rag-tag mix of brilliant people who gave money or poured in colossal time and energy to make the festival happen. It’s the people that make a place – and build a festival. It was “the people” who not only saved Greenbelt but re-established it as a distinctive annual gathering, a space to recover faith, grow solidarity in activism and blow you away with its programme.

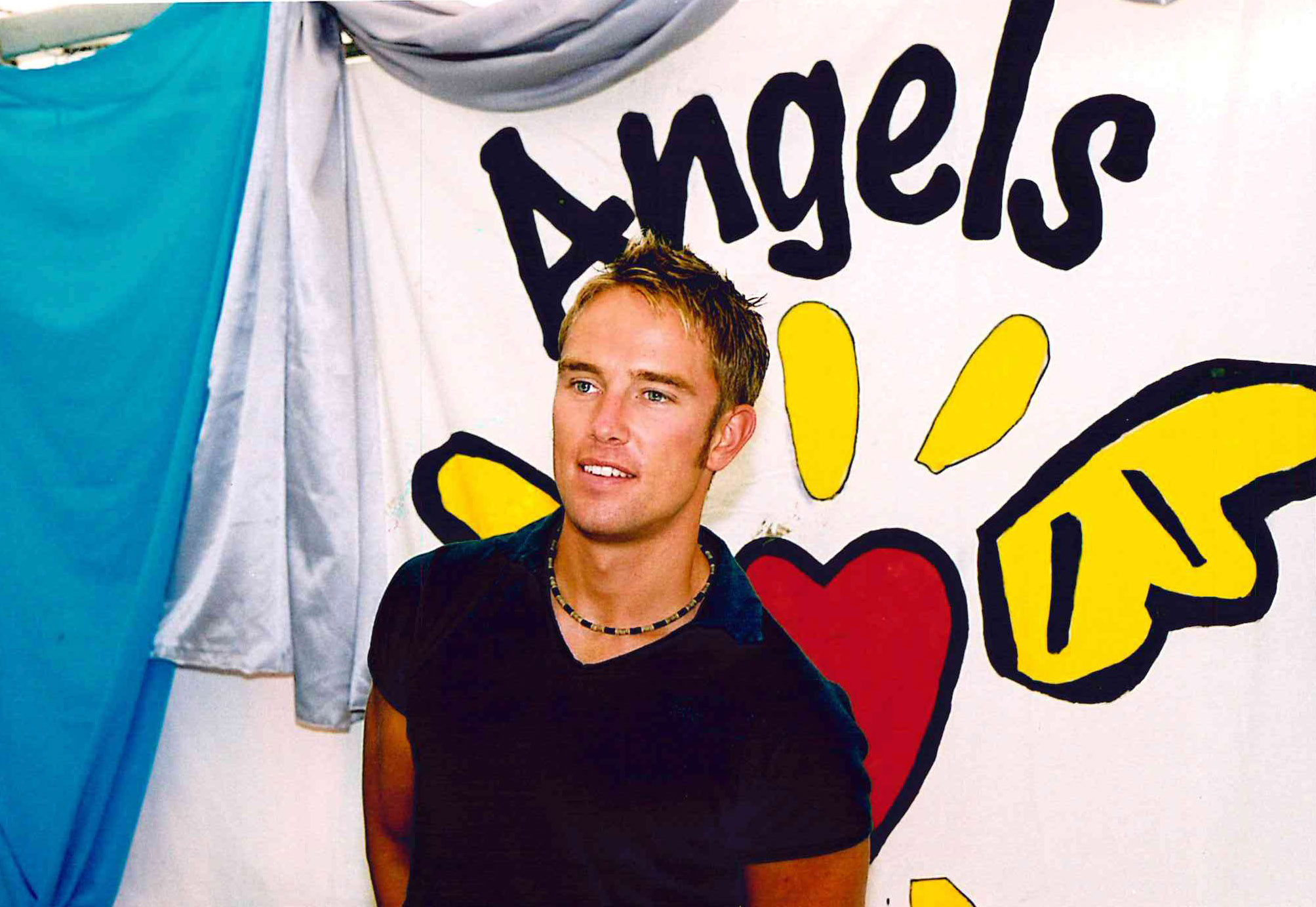

Simon Thomas, 2007

Start with Angels.

The idea of Greenbelt Angels formed in the 90s, from a previous festival fund-raising scheme – ‘Plotters’. It was then trustee Paul Wilson who was struck while dozing in a Mexican hammock at home, that people, Greenbelt Angels especially, wanted more Greenbelt and had more to give – maybe ideas, time to volunteer, or just being together and in-on all the festival news. We needed a shift to best support this! A heavenly host of hardcore Greenbelters started to get organised. A bi-annual week on Iona became a fixture. A news mag’ ‘Wing and a Prayer’ was posted out quarterly. An Angels weekend offered an annual dose of festival for the winter months. And a gorgeous 5pm festival preview, everyone together before doors opened on the Friday of each Greenbelt. What not to love? To keep this all firmly in mind, an “Angel” – Paul Bennett, who lived, no-joke, on ‘Angel Lane’ – joined the board of trustees.

And Angels gave money, enabling the festival to pay a growing staff team – relocated to an office at All Hallows on the Wall, in London. Or fund tickets to those who couldn’t normally get along. The point isn’t that Angels bailed out Greenbelt, though they remain a financial lifeline. It’s that to rebuild the festival, Greenbelt needed to grow and nourish community – starting with the Angels and spinning out from there.

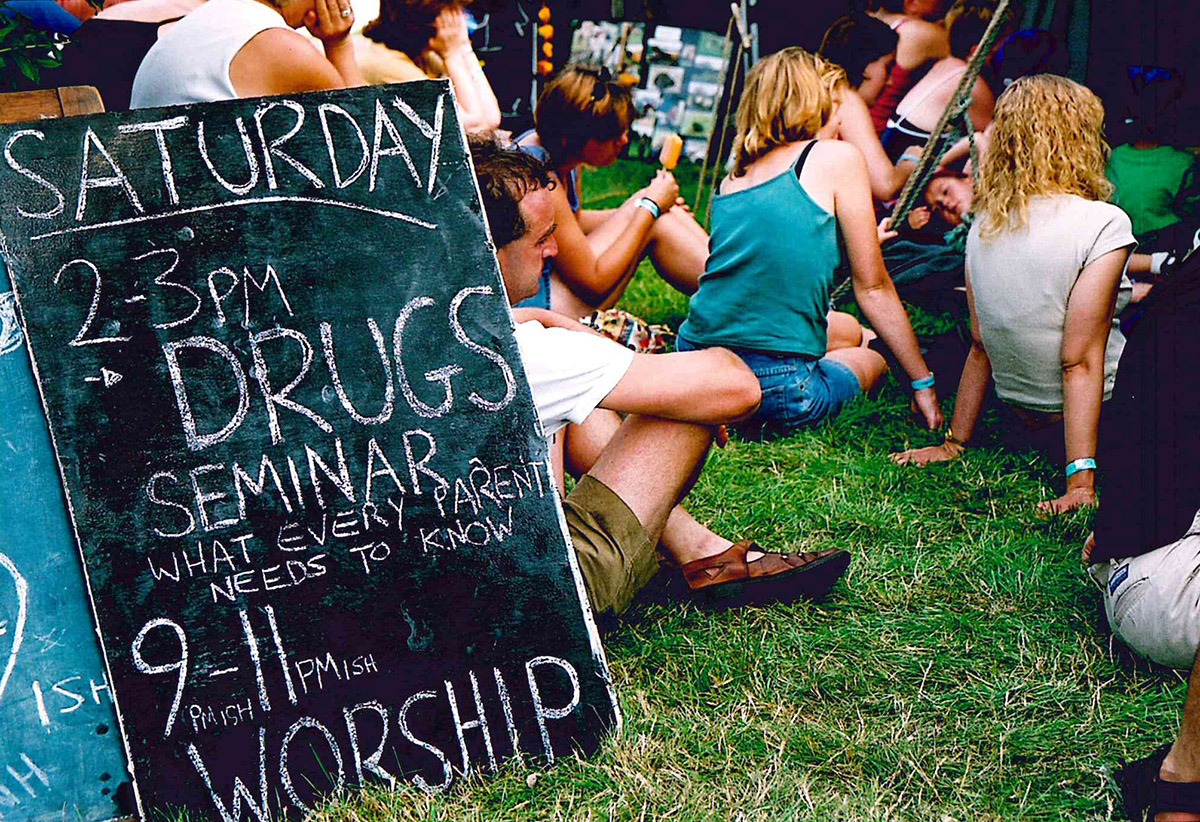

For thousands, Greenbelt involved a year of planning, making, and meeting, culminating in the weekender. This was activity directed, or overseen by staff – work finishing, and starting again at Greenbelt. For some, Greenbelt was proper New Year – the ending of something and beginning of the next. By the end of the decade organising groups had sprouted to assist all aspects of the festival. I wound up on various planning groups. A favourite was the collective producing Greenbelt’s “best of the fest” late-night show, ‘Last Orders’, meeting regularly to “plan” in the ‘Yorkshire Grey’, near the BBC.

Delirious, 2002

Festival late-nights were essential for those who split childcare, mooched with mates, or occupied the infamous ‘Tiny Tea tent’, missing the day’s carefully curated programme, and searching for some essence of Greenbelt. Night-time offerings from Paul Cookson’s ‘Twist’, Paul Powell and Cole Morton’s ‘Velvet Smoking Jacket’ or Pip Wilson and Martin Wroe’s legendry ‘Very Stinking Late Show’ all offered such joys. With Jude Mason ne Adam (Judeandandy), and producers James Cary, Helen Morant, Lynda Davies, and Simon Hildrew, ‘Last Orders’ featured headliners alongside new acts (Harry Baker, ‘Folk On’), interviews, and comedy, entertaining a packed ‘Centaur’, lingering into the morning. We had fun each festival over four nights and saw out the decade.

Lots of people found Greenbelt a space to grow life-saving groups that met throughout the year. Special interest or campaigning groups used the festival to revive connections and organise. Or a celebratory, safe space for, say, LGBTQI people typically ostracised or excluded by church. Or survivors of spiritual or religious abuse. Or environmental groups. Or spiritual directors. Or people pioneering alternative, “fresh” expressions of church. The festival grew community.

Some groups were even funded by the festival, the idea for ‘Trust Greenbelt’, a second hammock-based Paul Wilson eureka-moment. “Trust Greenbelt” – in part a polite request to Greenbelters concerned about the festival’s position on, well, on all sorts – was also an annual appeal, donations collected over the weekend. Rather than finance the festival, Trust Greenbelt gave grants for campaigns, artists, and performers, funding hundreds, giving away thousands (half a million pounds over the 10 years from its launch in 2005) – a gift for Greenbelters from Greenbelters.

Greenbelt has a history of highlighting campaigns. In a 2009 article, academic Gordon Lynch pushed Greenbelt to go further, and take a stand on Palestine. The festival already challenged Israel’s illegal occupation via artists and speakers. Led by Festival Director Beki Bateson Greenbelt embarked on a unique three-year campaign to highlight the occupation in the land “once Holy” across the programme. A series of visits in 2010 and 2012 provoked further actions by Greenbelters and artists, working to challenge thinking and change behaviour. Work continues at every festival.

Greenbelt at Cheltenham benefited from the racecourse, maybe its own mainly sunny micro-climate, and a backdrop of Cotswold hills to park your tent. Led by Andy Thornton then Beki Bateson and chairs Jude Levermore and Karen Napier, Greenbelt flourished. Sure, the festival provoked all manner of proposals for Greenbelt 365, all-year-round, a gnawing ambition for some which never materialised. But more importantly the festival sparked life-long friendships, birthed artistry and ideas, galvanised and politicised, reworked faith, and shaped careers and vocations. And the community grew festivals.

Near the end of the decade in June 2009, Solas, a midsummer arts festival at Wiston in Scotland happened. Two years later in 2011, Wild Goose festival launched in the US. Then Bet Lahem Live in Bethlehem, in 2013. Festivals you may spot happening this summer. All festivals with their roots under the sky at Greenbelt.

Communion, 2002