To celebrate our 50th anniversary, we’ve asked some of the folk who’ve helped bring Greenbelt Festival to life over the last 50 years to write a little something about their festival experiences. One blog post per month, reflecting on one decade at a time.

Last month, Bev Sage wrote about the 1980s. This month it’s the turn of Dot Reid and Nick Welsh to take us back to the 1990s, a decade that almost saw the death – and, in another way, the rebirth – of Greenbelt.

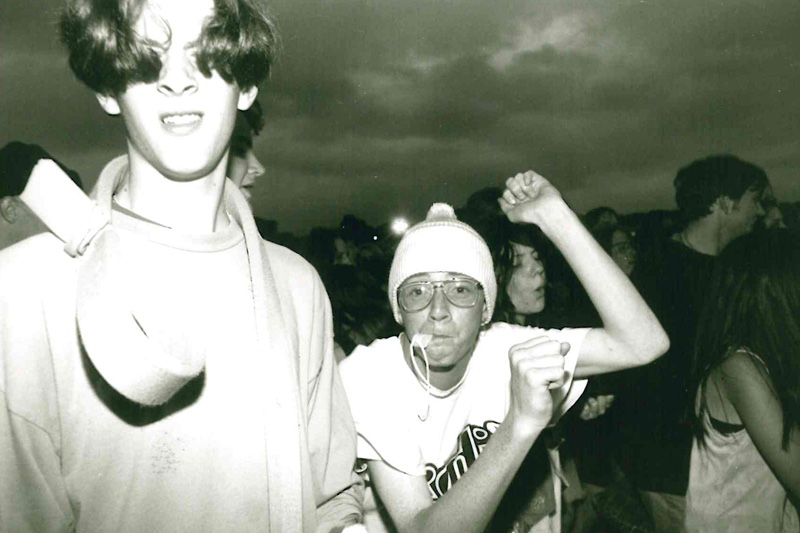

1991 Greenbelt MainStage, Castle Ashby

What to say about Greenbelt in the 1990s? Maybe the Festival’s most difficult decade, and certainly the one in which it had a near-death experience. A decade that began with the end of the Cold War and the release of Nelson Mandela, and ended with the demise of Thatcherism and the hope of New Labour.

But in Greenbelt-land, it was a tale of two halves: on the one hand, the Festival had two site moves – to Deene Park (1993) and Cheltenham Racecourse (1999) – while declining audiences and finances kept the Board up at night; on the other, it had some of the best music to ever grace our stages.

Nick Welsh was working as the in-house promoter at a venue called The Junction in Cambridge, where he’d been busy booking acts like Radiohead, Manic Street Preachers, Jamiroquai and Stereo MCs. Dot Reid was Chair of the Greenbelt music committee, a partner in Sticky Music (who recorded albums in the 1990s with Iain Archer, Juliet Turner and Lies Damned Lies) and busy having babies. The two of us were thrown together by the Festival’s then General Manager, Martin Evans, who (rightly) thought we’d make a good team.

In the late 1980s and early 90s, Jonathan Cooke and others started booking what were then called ‘special guests’. So, alongside traditional contemporary Christian acts such as Amy Grant and Steve Taylor, up popped The Alarm, Bob Geldof and Des’ree.

Our decision to continue down this road seemed a natural one. There were no more ‘special guests’ – just great artists. We had only a few rules. We aimed to book bands who played really good music (that sounds obvious now, but it wasn’t so much then). And although we weren’t looking for a Christian ‘connection,’ we wanted quality and values that resonated with Greenbelt and Greenbelters.

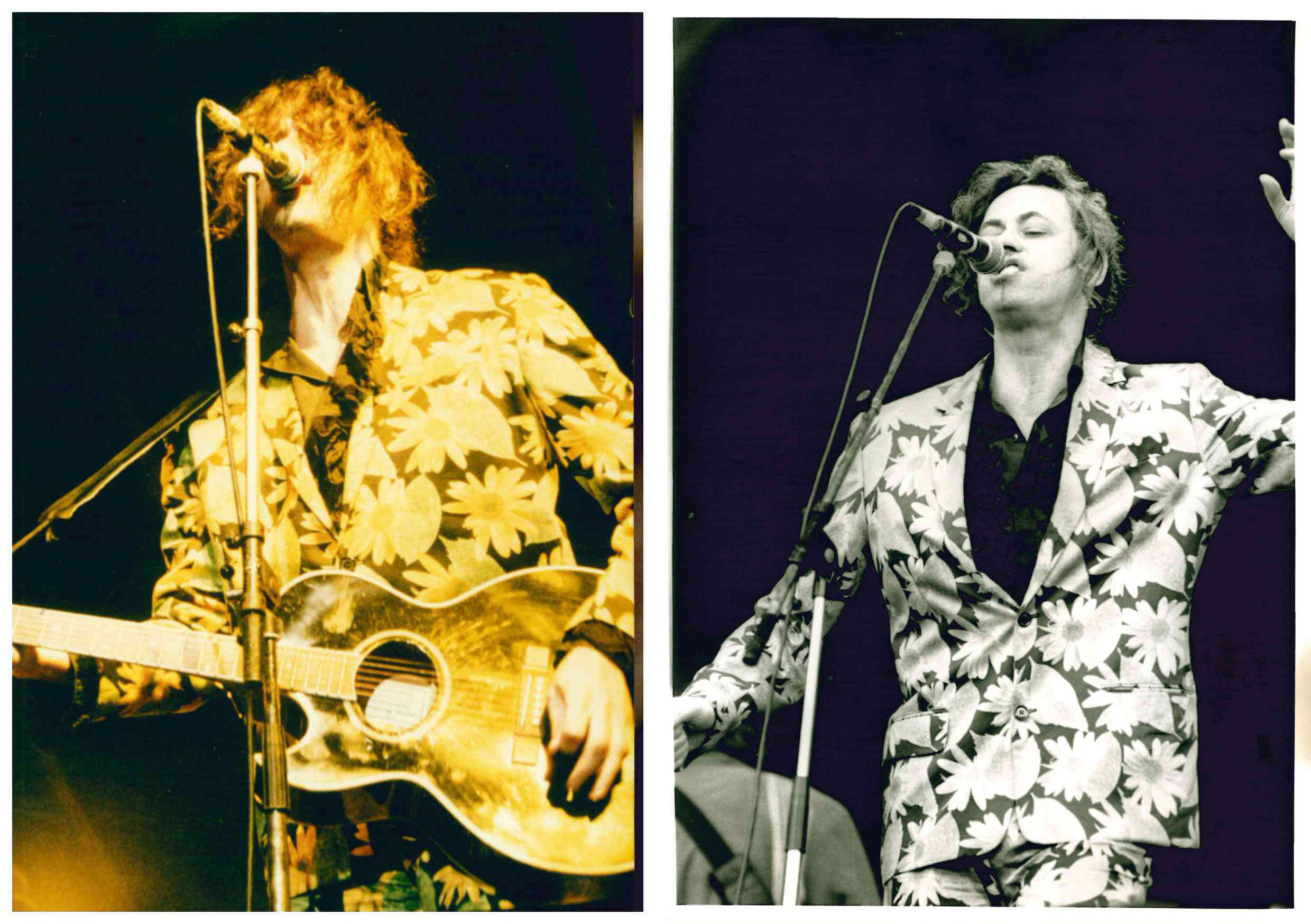

1992, Bob Geldof and the Happy Clubsters at Greenbelt Festival

What were those values?

Greenbelt had always taken risks and was positioned to the left of most church congregations. It championed the causes of Palestine and Nicaragua; it created a safe space for gay and lesbian people; it welcomed alternative voices. It was also beginning to endorse more obvious political positions – the long-term partnership with Christian Aid putting campaigns like Jubilee 2000 at the Festival’s heart. And we wanted to find great artists who would support those causes and who would give a ‘Christian’ Festival a chance.

We had a good system. We would speak on the phone (there was no email back then) about eight times a day and have a conversation that went something like this:

Nick: “Hi Dot.”

Dot: “Oh, Hi Nick.”

Nick: “I want to book ‘so-and-so’. I’ve spoken to their people, and they can do it. I want to offer them £xxxxx”

Dot: “OK, can you persuade them to do it for £xxxx?”

Nick: “Yep, I’ll try. I’ll keep you posted.”

That’s how it worked – no committee meetings, just gut reactions. Should we book Jah Wobble’s Invaders Of The Heart? Yes, of course we should – they’re incredible. Would the James Taylor Quartet go down well? Yes, of course they would – they’re brilliant.

What about Goldie, 808 State, Lamb, Sneaker Pimps, Incognito, Corduroy, Credit To The Nation, Asian Dub Foundation, The Blind Boys of Alabama, Courtney Pine, Brian Kennedy and Carleen Anderson from Young Disciples? We thought so.

“Ladies and Gentlemen, please give it up for Moby!”

The main disadvantage we had when trying to book these kinds of acts was, of course, money. We didn’t have any. What we did have, though, was timing. The August bank holiday weekend coincided with Reading Festival, which was only a couple of hours down the road. Sometimes, acts playing Reading could be persuaded to play Greenbelt ‘on their way home’. This meant we could book bands who were a) in the country, b) out that weekend, and c) might do it on the cheap.

Moby was a good example of our making an approach through the back door and not via the artist’s agent. He was playing Reading, and after many calls and much to-ing and fro-ing, Richard Melville Hall (for it is he) was booked in 1995. He enjoyed it so much that he came back the following year.

Then, the floodgates opened, and in came Midnight Oil and then, later, over the next decade and more, The Polyphonic Spree, Kate Rusby, Athlete, Jamelia, Eddie Reader, Jazz Jamaica, Aqualung, The Proclaimers, Corrine Bailey-Rae, Gilles Peterson, Maria McKee, My Morning Jacket, José González, Mavis Staples, Michael Franti and Spearhead and Coldcut. (And Chas & Dave.)

Once these artists agreed to play, they often loved it. After all, the audience wasn’t drunk, they were treated well and the backstage crew were as professional as at any festival. This was important, because we knew they’d ‘report back’ to their managers, agents, record companies and, crucially, other acts we wanted to book: “You know that Christian Festival Greenbelt? You should go play there — it’s great.”

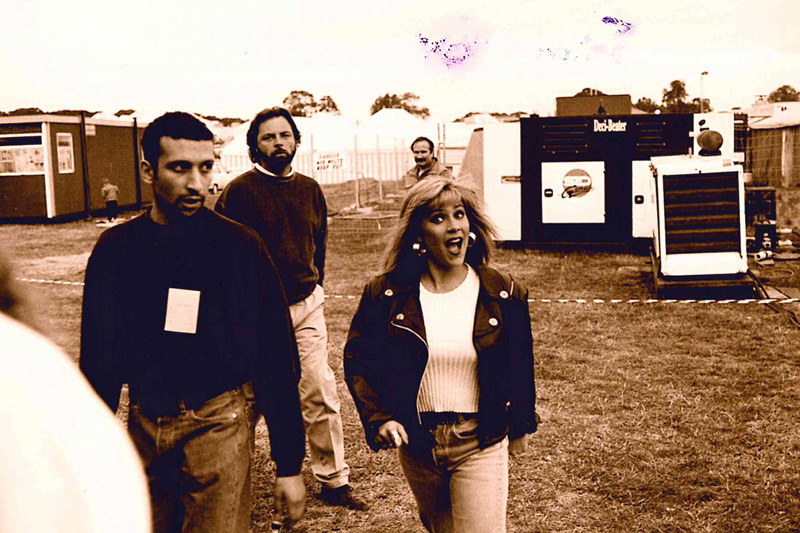

Girl bands were also a thing in the 1990s. We didn’t book any, but we were increasingly conscious that Greenbelt’s line-up looked very male. At least that’s our excuse for a booking that broke all of our rules. Former Page Three model Samantha Fox had found God at Holy Trinity Brompton (HTB) in London and she announced it at Greenbelt. It was a booking made against everyone’s better judgement (including Nick’s!), but still, it might have been the only time a performer arrived by helicopter, along with a posse of bemused paparazzi. As Samantha belted out a scantily-clad ‘Naughty Girls Need Loving Too’ in the Big Top, a surprising number of critics were inside that tent.

Samantha Fox at Greenbelt, Deene Park, 1994

Changes

But the invisible backdrop to these great festival memories was more worrying. The days of mainstream church youth groups – the backbone of the Greenbelt audience in the 1980s – were waning, like church affiliation more generally. Church energy and growth were mostly in evangelical and charismatic circles. Churches with lots of young people were becoming more conservative, and a bit suspicious of a festival that didn’t invite the big figures of the ‘movement’ to appear on its stages.

While Holy Trinity Brompton (in London) and the mighty Alpha course were conquering the church, Greenbelt was theologically showcasing the post-evangelical and the alternative worship movement, with NOS (The Nine O’Clock Service) and the Late Late Service.

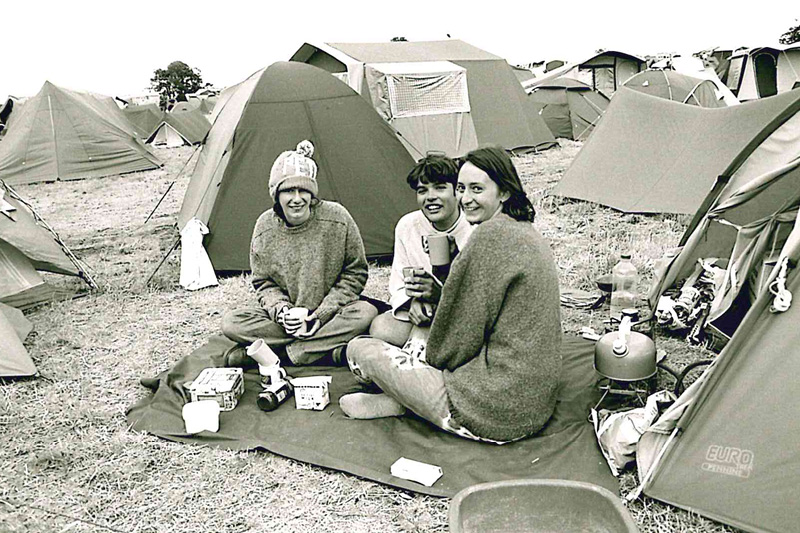

Worship was always central – who could forget rehearsing 50 singers, 50 drummers and 50 dancers (on top of portacabins) for the ‘Field of Dreams’ communion and burying our hopes and dreams in a clay pot at Deene Park? We wonder when we might dig them up again – maybe while some of us are still alive and might remember which tree we buried them under!

Looking back, no doubt we all could have been more conciliatory. But at the time, it felt important to represent a different kind of spirituality that had its deep roots in a shared humanity. But audiences were getting smaller, and the rains came, leading to another financial crisis after the 1997 festival. The Greenbelt Board realised we could no longer afford to create a village every year from scratch with enough infrastructure for 20,000 people. So, in 1999, Greenbelt moved to Cheltenham Racecourse, which had running water, electricity and proper toilets! The problem was, it took a few years before everyone else followed.

1999, Teatr Biuro Podróży perform at Greenbelt’s first festival at Cheltenham Racecourse

Only a few thousand were there to hear them that year in 1999, but as we stood and listened to The Blind Boys of Alabama, Asian Dub Foundation, Bruce Cockburn and the most wondrous, ‘bassiest-ever’ bass of Jah Wobble’s Deep Space (a personal favourite) booming around the Cotswolds, we wondered if this was our last hurrah.

But two other significant things happened in the 1990s that meant we were able to come back from that near-death experience: the Greenbelt Angels were born and the Festival began a long-term partnership with Christian Aid. And maybe this is the place to acknowledge how crucial the Angels were (just 800 of them initially), plus a few Archangels (who lent us money) and a dogged Irishman called Kevin McCullough, who persuaded Christian Aid to stick with Greenbelt through the tricky bits. Greenbelt wouldn’t have survived into the millennium without them.

These days, no one bats an eye when Black Rebel Motorcycle Club, Sinead O’Connor, Newton Faulkner or Kae Tempest headline the Festival. The only questions that need to be asked are: Are they any good? Do their values chime with ours? And will they create more magical Greenbelt memories?

1998, Greenbelt’s last year at Deene Park

Dot Reid is a Senior Lecturer in Law at the University of Glasgow. Nick Welsh is Head of Communications at Amos Trust.